Housing wealth, not bursaries, explains much of private school participation for those without high incomes

By Jake Anders and Golo Henseke

Although less than a tenth of children in Britain attend private schools, who goes matters to all of us. This is because of the considerable labour market advantages that have persistently been associated with attending a private school, including recruitment into the upper echelons of power in British business, politics, administration and media. As a result, in recent work published in Education Economics we looked into who send their children to private schools. In brief, despite all the talk about bursaries, public benefits and attempts at widening participation, who goes to private school remains as closely tied to family income and wealth as it did at the end of the 1990s. This casts doubt on accounts of real progress in opening up the sector to a more diverse student body.

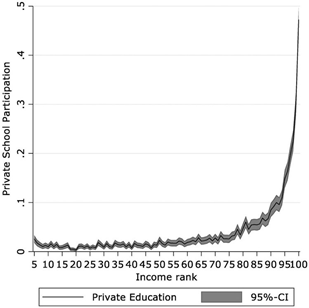

In the paper we demonstrate quite how concentrated private school attendance is among the highest levels of household income (see image). The proportion of children attending private school is close to zero across the vast majority of the income distribution, and doesn’t rise above 10% of the cohort except among those with the top 5% of incomes. Only half of those in the top 1% send their kids to private school.

Income concentration of private school participation, 1997-2018.

On one level this is unsurprising. Sending your child to a private school costs a lot of money: in 2018 average annual fees were £14,280 for day schools and £33,684 for boarding schools. Not many people have more than £1000 per month available to spend on school fees unless they have some of the highest incomes in the country. But what about those who do attend even though they’re from families with incomes below these levels, even if there are not many of them?

One potential explanation, much flaunted by private schools themselves, are bursaries. Indeed, our analysis found that about 1 in 6 private school pupils received some form of financial support such as bursaries or fee reductions – does that explain our observation and suggest these are doing real work to open up the private school sector to a wider stretch of society? Sadly, not: it’s not the case that all kinds of financial support are targeted at lower income groups (some are academic or music scholarships, for example) and if we focus on those outside the top income decile, a large majority – up to four out of five children – are not receiving grants or bursaries.

Furthermore, among those who received it, average financial support was around £4,900 in 2011-2018. This is little changed from earlier periods that we also analysed and, because of rising fees, paid for a smaller fraction of those fees (35% compared with 57%) than it did in 1997-2003. Taken together, these cast serious doubt on the idea that this is making a big difference to widening participation in private schools – or that it’s playing a growing role in achieving this in recent years.

As such, we set out to explore other sources of potential financing for private school fees that might explain their affordability at lower levels of income: housing wealth and how it has grown in recent decades. We find that a 10% rise in a family’s housing wealth raises private school participation by 0.9 percentage points. This is actually similar to the association we see between family income and private school participation – among those with high levels of income. However, unlike the income link, the role of increased housing growth is evident much further down the income distribution. This suggests that access to wealth, rather than support from bursaries and grants, is playing an important role in helping these families send their children to private schools.

These findings have clear implications for things that need to change. Our findings imply that while existing bursaries offered by private schools do perform a somewhat progressive role, they are far too small and scarce to make much of a real dent in private schools’ exclusivity. Means-tested bursaries would need to expand considerably in reach and scale, and the selection criteria should take into account family wealth, not just income. Private schools need to up their game dramatically in this respect, otherwise calls for externally imposed reforms to effect real change will only grow louder.

This research was covered in an article by The Observer.