The popular revolt against open borders that swept across Great Britain and the United States last year has not, so far, crossed the Channel. In The Netherlands and France mainstream parties and candidates backing the EU and globalization more broadly won elections during the first half of 2017.

The media tried to explain this pattern, by pointing out that the link between age and support for “drawbridge up” parties was completely different in France. While the elderly voted for Brexit and Trump in the UK and the US, in France it was the young and middle aged groups that backed Le Pen, they said. The young, allegedly, turned to Le Pen in massive numbers because of high youth unemployment, job insecurity and lack of prospects. The unspoken conclusion was that young people in Britain and the US fare better, are more optimistic about the future and therefore saw no reason to rebel against mainstream parties.

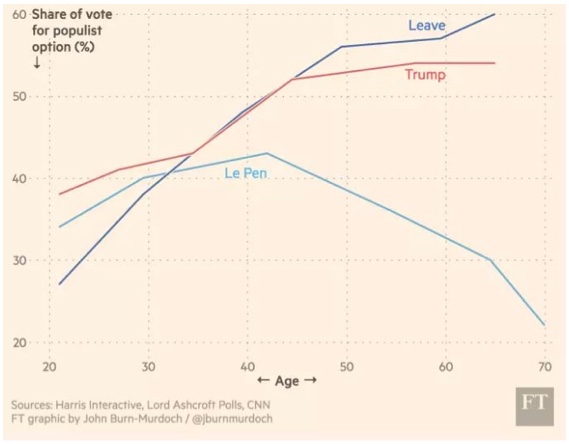

However, if we take a close look at the data we see that it is not so much the young people who behave differently in France, but the elderly (see Figure below). While young people and middle aged groups have pretty much the same voting behaviour as their counterparts in the US and the UK, the French seniors show much lower levels of support for the populist option. The contrast is particularly stark among the 60+ group.

Source: Financial Times

The electoral preferences of French pensioners are echoed in The Netherlands. There too, those who were 65+ were least willing to cast their vote for the PVV of Mr Wilders, the Dutch equivalent of the Front National (only 6% voted for this party in the March 2017 elections, as opposed to 8% among the 18 to 24 year olds).

To my knowledge, this remarkable contrast has gone unnoticed. It begs the question why the elderly vote so differently on opposite sides of the Channel. Socio-economic explanations don’t seem to apply. While the income of the elderly in Britain lagged behind that of their counterparts on the continent for a long time because of relatively modest state pensions, more recently their position has dramatically improved. Today pensioners have slightly higher incomes than working households, due in no small part to the triple lock policy instituted under the previous government. Pensioners are also by far the most affluent group in Britain, as they benefited disproportionately from the rise in house prices from the 1990s. They have therefore largely caught up with their peers in France and The Netherlands, who are in an equally privileged position.

The only explanation for which I can find some evidence is a difference in the level of nationalism. The importance that people attach to being British is one of the strongest predictors of voting to leave the EU, as our provisional analysis of early released Understanding Society data show. Feelings of attachment to one’s nation therefore seem to play an important role in determining voting behaviour. If we then look at cross-national differences, we see some remarkable patterns (see the figure below). The percentage of elderly (people born before 1955) expressing high levels of pride in their nation is twice as large in the UK and the US (approximately two-thirds) as in France and the Netherlands (one-third). Admittedly, the levels of national pride are also higher among the other age groups in the English-speaking countries but the difference among the elderly is the most pronounced.

Perhaps the different wartime experiences can explain this contrast. Although only the very old today have actually endured the war themselves (and many of them only as children), the parents of the 65-plusses are likely to have had a lasting impact on their outlook. Possibly, therefore, the elderly in France and the Netherlands became permanently more allergic to nationalism and suspicious of politicians with protectionist agendas due to their parents’ generation’s experience of the German occupation and its accompanying belligerent nationalism. In contrast, patriotism and nationalism tend not to have the same negative connotations in Britain and the US, where the terms might be associated with victory, glory and solidarity rather than aggression, oppression and bloodshed. If true, World War II certainly casts a long shadow into the present.